The ‘natural language’ of machines is binary. Binary is a base-2 numeral system, represented by 0s and 1s, and is fundamental to how computers function as it directly corresponds to the on/off states of transistors, electronic hardware at the root of all computers. Formally, Alan Turing developed the concept of a Turing machine, represented by an infinite roll of tape divided into cells, with each cell holding a symbol from a finite alphabet (typically and for example the set X where X = {blank, 0, 1}), with a read/write head, a state register, and a transition function. The read/write head can only edit cells and move between them. The state register holds the current state (instructing the read/write head on how to react given a specific cell), and the transition function (which contains a set of rules) allows for state transitions. Given an infinite tape, a Turing machine, using binary 0s and 1s, can represent any computable function or algorithm. We say that a language is Turing complete if it can compute any effectively solvable function, assuming unlimited time/resources. Practically (but not theoretically, as we do not have infinite RAM nor infinite time), most programming languages are Turing complete.

Now while computers at their root use binary, programs, written by humans, are not - to do so would be far too onerous, so we created programming languages. These are ways to abstract the machine code such that many 0s and 1s could instead be represented by commands such as ‘read’ and ‘write’. There is a hierarchy to these programming languages, from low-level languages such as assembly to high-level ones like Python, with intermediate layers e.g. assembly or bytecode bridging the gap, each having their own strengths and weaknesses. C, for example, permits direct memory management, which allows for finer control and more efficient programs, but presents greater dangers in that one mistake could leave code vulnerable to memory exploits.

C is also an example of a language that requires programs to be compiled into a binary executable that the computer can action - that is, the human-readable C code is transformed into machine-readable instructions through preprocessing, compilation into assembly (a lower level programming language much closer to machine code), and then the resulting assembly code is assembled into object code, consisting of 0s and 1s - binary, and thereafter linked to an executable. Compare this to Python, which uses an interpreter that compiles human-readable Python code into bytecode, an intermediate form that is then executed by a virtual machine, called the PVM, which automagically handles related lower-level machine tasks, allowing for a dynamic approach to programming.

At its root, though, all computer processes and thus the language of machines is 0s and 1s - binary. This extends to communication itself, for while traffic protocols and network packets might be far removed from binary and are in fact more akin to natural human language in the sense that we can understand it by inferring meaning, once those self same packets are transferred over the wire they are first transformed down the hierarchy into raw 0s and 1s and that data is serialized into binary signals for transport. When those electronic/optical signals hit a target machine they must then be programmatically transformed up the hierarchy of language following various protocol rules such that they can once again be crafted into usable human-readable network packets.

If the natural machine language, its ur-language, is binary - then what is it for LLMs? At first this seems like a silly question - underlying an LLM is compute, and for anything computable, binary is the ur-language. However, consider LLM internals, which are tokenized text embedded in n-dimensional vector space. Strictly speaking, they are indeed stored and computed in binary floating-point form in memory and computation - but were you to speak ‘binary’ to an LLM, i.e. translate a command into pure binary and use that as your input prompt, you would find yourself fast running out of context memory by exceeding your token length.

The question then becomes - what is the most token-efficient language for LLMs? Considering that most frontier models are either Western or Chinese, the answer seems obvious - English or Chinese. In terms of natural languages, English is more token-efficient than other European languages, and far more efficient than non-western languages, due to tokenizer optimization for latin script and the majority of training data being in English. One exception to this rule seems to be Chinese, which also has a wealth of training data. More importantly, Chinese characters often convey more meaning with fewer tokens, which gives us some insight as to how one might go about engineering a more efficient LLM language.

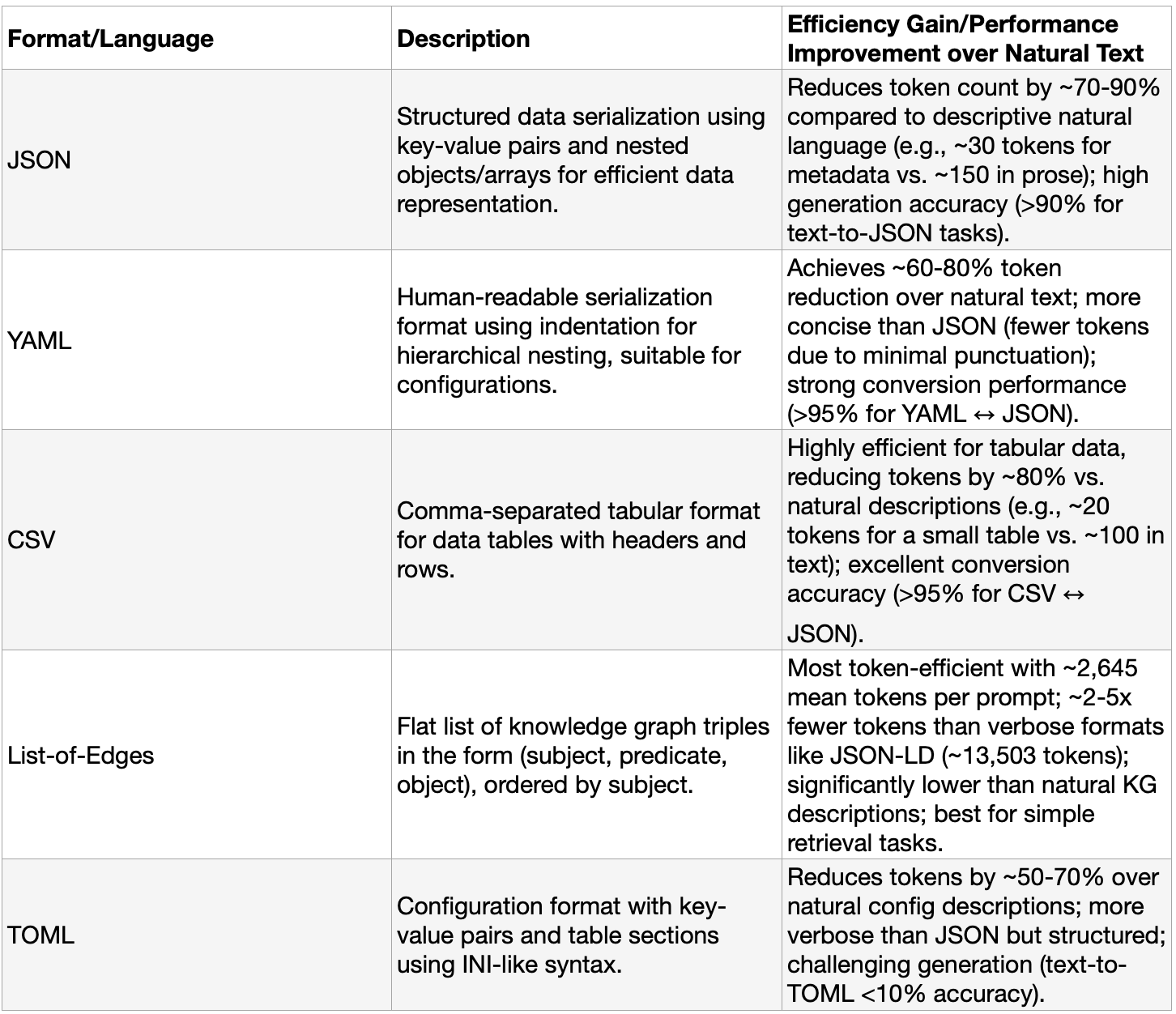

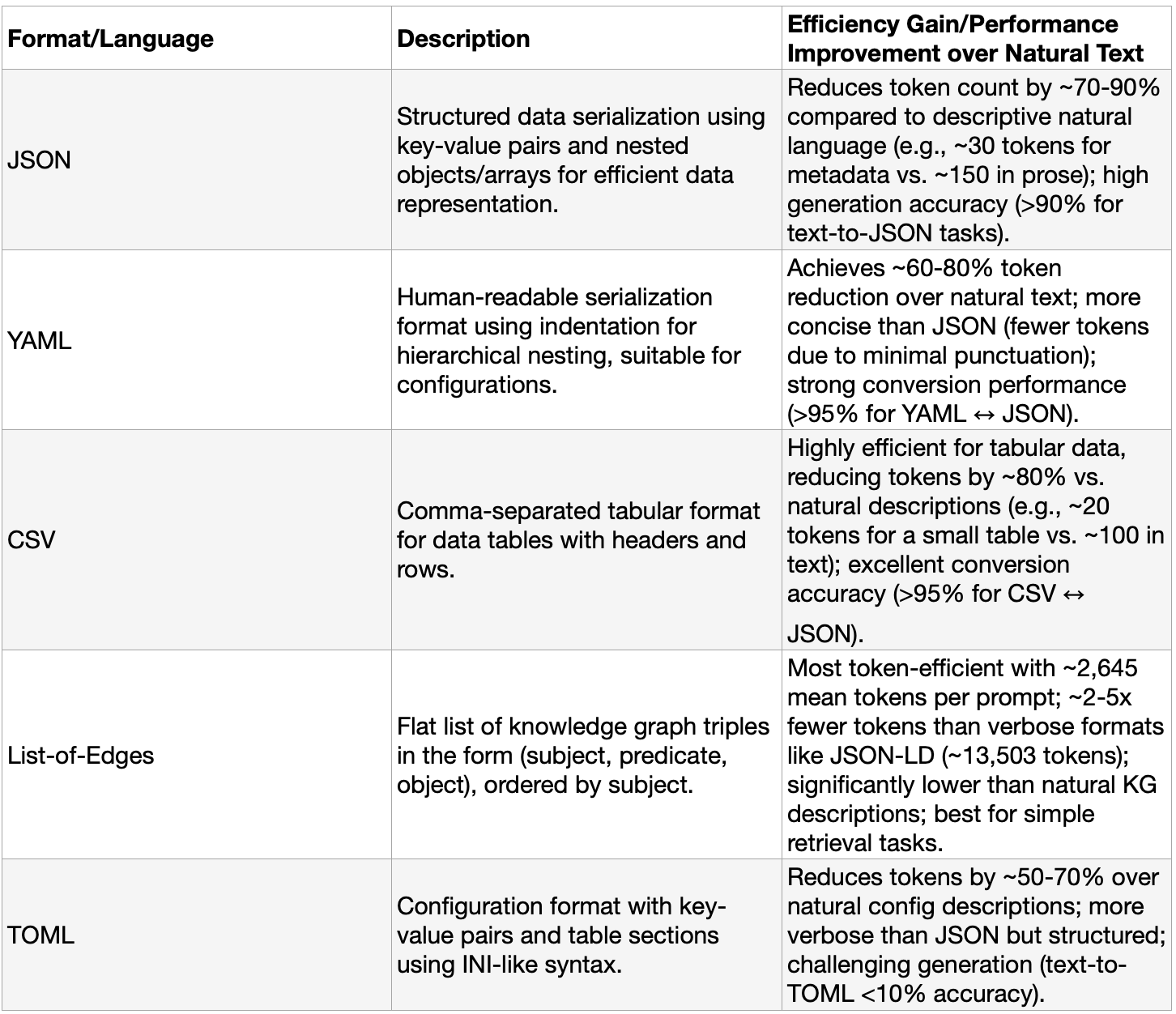

Prompt engineers have come up with a number of innovations. Structured key:value pairs like JSON or YAML do quite well, but they require context engineering, i.e. one first has to provide a set of instructions on how to interpret the data. Markdown can be used for readable formatting e.g. lists or headers; XML provides tagged structured for delimiting content e.g. <body>qwerty</body>; CSV excels for tabular data i.e. spreadsheets. These, too, require context engineering to load certain parsing rules into the LLMs context memory. Researchers have gone yet further and made noticeable improvements, increasing token efficiency but often constrained to specific tasks such as coding. A small table can be found below:

Sources: StructEval: Benchmarking LLMs’ Capabilities to Generate Structural Outputs KG-LLM-Bench: A Scalable Benchmark for Evaluating LLM Reasoning on Textualized Knowledge Graphs

What all of these ‘languages’ have in common is that they serialize data, meaning they transform content, such as in this case natural languages like English, into standardized formats; and they make use of delimiters (e.g. colons, commas, brackets). These predefined formats demonstrate a remarkable token efficiency when compared to natural language, sometimes achieving >70% token count reduction. This sometimes comes at the cost of having to prime the model with an instructional prompt, but this is more often than not explicitly necessary for unique schema - well-known formats like JSON are already well understood by frontier models due to training data. However, for open-weight models, an explicit instructional prompt for a non-standard language can be supplied during inference as a system prompt.

One important caveat is that these transformations risk semantic degradation, in that improper data serialization by way of poor prompting (bad context engineering) can lead to a ‘lost in translation’ effect. This could negate the token efficiency savings and in the worst cases could even lead to using more tokens due to having to repeat prompts over and over again. Therefore it’s important that the model both have the capability to understand explicit instructions and that the prompter know how to provide a suitable prompt. Thankfully, now in 2026 even small models have more than enough reasoning capability; humans, on the other hand, have always been the weakest link in the chain…

Theoretically, one can imagine a hyper-optimized super-token-efficient structured language format that takes raw data and serializes it such that semantic meaning is perfectly preserved while token length is shortened to its absolute minimum. This aligns with an idea from information theory - Kolmogorov Complexity, which refers to the length of a program that produces a given object. In layman’s terms, this measures how random a string is - the more random, the higher its Kolmogorov Complexity. This is important for us precisely because an absolute minimum Kolmogorov Complexity would necessarily mean a better, more efficient and more effective, LLM language, implying maximum compression without semantic loss. Such a perfect language would certainly qualify as a natural apex AI-to-AI language. While incremental improvements to known good language formats are definitely on the horizon in that discoveries and innovations are being actively pursued by researchers, at the root of it all is the bare metal hardware that has to compute everything, and that there is reduced to pure binary.

Turtles all the way down.